How you can tell you’re in love with baboons

Joselyn Mormile knew she was in love with baboons the day she went into town to do some shopping in the South African province of Limpopo. She had been working at the C.A.R.E. baboon rescue and rehabilitation center, located near the Kruger National Park. C.A.R.E. is somewhat remote, and volunteers and workers don’t usually leave the compound much, often just once a week to get supplies and such.

A chacma baboon! What’s not to love? Photo © Amanda Harwood

It was on one such trip, at a stop to get gas, when she and her friend spotted an adorable little human child nearby. Before she knew what she was doing, she rapidly smacked her lips together at the youngster. “I can’t believe it,” she told her friend, “I just lip-smacked* at this little kid!” Her friend turned to her and said, “Well, I just made a play face**!” They both agreed they should probably get out a little more.

* Lip-smacking is a friendly gesture used by baboons and many other Old World Monkeys.

** A play face (which is seen in many species of primates, including baboons) is a relaxed, open-mouth expression with the teeth more or less covered.

[Full disclosure: While working with some baboons in a sad little lab back in the 1980s, I fell in love with them, too, especially a gentle fellow named Danny who was prone to epileptic seizures about once a month. I knew I was in love when I found myself doing the same thing Joselyn did: while out shopping one day, I unconsciously lip-smacked in greeting to a cute human baby. Pretty embarrassing. Apparently, it’s easy to forget that not all humans are fluent in baboon.]

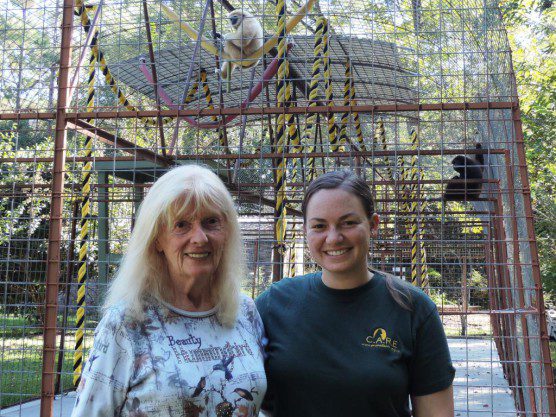

Joselyn Mormile visited the IPPL sanctuary last week and helped make enrichment devices for our gibbons.

Joselyn and her mom visited the IPPL sanctuary last week, and Joselyn shared her experiences volunteering, working, and studying on behalf of South Africa’s baboons. She just completed an MSc degree in primate conservation from Oxford Brookes University this past September (dissertation title: “An Ethnoprimatological Approach to Assessing the Human-Baboon (Papio ursinus) Interface in the Suburbs of Knysna, South Africa”); she plans to return to the same community next September for her PhD research.

But Joselyn first encountered South Africa’s chacma baboons during a one-month volunteer stint at C.A.R.E. starting in February 2011. She was asked to return later in the year, which she did in September, staying on for about 10 months as a veterinary nurse and clinic director for some 600 resident baboons. She was there for the terrible fire that destroyed the clinic building and resulted in the death of C.A.R.E.’s founder, Rita Miljo, and three of her favorite baboons. Thankfully, although C.A.R.E. has gone through a difficult transition period, the center is flourishing, recently releasing a troop of rescued baboons into a lush wilderness area.

Chacma baboons are hardy and adaptable, but their habitat is increasingly being encroached upon by humans. Photo © Amanda Harwood

She left C.A.R.E. to take a post as research assistant for a PhD student studying wild but habituated baboons in South Africa’s Soutpansberg mountains, north of C.A.R.E. For eight months she took baseline behavioral data on all 80 troop members. One element of the study was predator-prey relations; baboons are prey for leopards and hyenas, but predators, as she witnessed, upon duikers (small antelopes) and guinea fowl.

But for the past year she has been her own lead researcher. She began with seven months of classes at Oxford Brookes, studying biodiversity, captive primate care, conservation education, field methods, and a list of et cetera, after which she carried out a field project into human-baboon relations.

A baboon in your backyard? Joselyn plans to continue her studies on human-baboon conflict in suburban South Africa. Photo © Joselyn Mormile

The town of Knysna (pronounced NIZE-nuh) is on the coast about 300 miles east of Cape Town. It is a wealthy community with many British, French, and Zimbabwean expats, as well as retirees and people looking to get away from the aggravations of city life. It is surrounded by the Garden Route National Park, but tracts of suburbia are increasingly extending into the natural wooded landscape. Within the last two years, baboons evicted from their original homes have found themselves in conflict with their human neighbors, and Joselyn spent 11 weeks conducting questionnaires and interviews to see how the people were feeling about that

It turns out that very few researchers have examined the human-baboon interface in the suburbs. Most studies of human-baboon conflict center around agricultural problems (“crop raiding”), but as the human population continues to expand, Joselyn said, we can expect more and more issues to surface in urban settings. The people she interviewed often described themselves as “angry and frustrated” about the presence of baboons. Her interviewees had come to the peaceful town to do what they wanted, when they wanted (including leaving their windows open to the balmy breezes at all hours), and had not counted on hungry baboons entering their houses. The people were not familiar with baboons and frequently viewed them as threats (regardless of the actual negligible risk to human life and property these animals pose).

I don’t think Shirley (left) asked Joselyn if she thought gibbons were cuter than baboons. We all have our biases…..

As a result of her studies, however, Joselyn was able to help design a Baboon Management Plan for Knysna, which was approved this past August. The plan involves establishing baboon monitors (four in each of two areas) who would be responsible for using non-violent means to keep baboons out of suburban tracts, setting up baboon-proof trash bins, and educating the public about effective ways to deter baboons from their own property.

Maybe the human residents of Knsyna will eventually learn to speak a little baboon, too.