Meet Blair, our summer intern

How do you get an internship at IPPL’s gibbon sanctuary?

By being talented, persevering, and dedicated to animals—just like Blair St. Ledger-Olson, who is staying here several weeks this summer and is working on a project for her bachelor’s degree in Environmental Studies at Hollins University, in Roanoke, Virginia. Maybe having studied the rare Peaks of Otter salamanders doesn’t hurt, either.

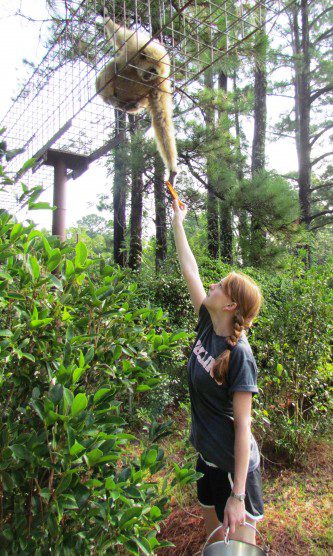

Every morning Whoop-Whoop waits for Blair to bring him his sweet potato in the aerial runway where he likes to hang out. He likes to make her stretch.

She always knew she wanted to work with animals, but the vet track did not appeal. (“I don’t think I could ever put an animal down,” she says. “Plus fear of needles.”) She grew up in an animal-friendly home, though, with dogs and cats and horses. She says that her dad even affectionately refers to Blair and her mom as “witches”—in the nicest possible sense of the word, of course, because of their intuitive connection with all kinds of animals. The pair of them would often rescue stray dogs as well as injured birds and foxes. (OK, I get it: the “Blair Witch.”)

IPPL does not typically offer internship opportunities, but Blair came highly recommended by our long-time friends and allies at the Animal Welfare Institute, where Blair had interned previously. She has a lot of experience working on behalf of animals from behind a desk, both at AWI and in the office of U.S. Senator Mary Landrieu (D-LA), where Blair conducted research for legislation on environmental issues, especially concerning the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster.

Blair prepares the gibbons' breakfast buckets.

But she plans to pursue a master’s degree in wildlife ecology, so this summer she wanted some hands-on animal experience—and she’s getting it. She has spent her days shadowing IPPL’s animal care staff, helping with feeding, cleaning, and repairing climbing structures. She’s learning how to operate our extensive system of aerial runways, and she’s learning how to “read” our gibbons and recognize their individual songs and personalities.

She also needs to do an animal behavior project for her senior thesis. Right now she is thinking of looking at the reactions of wild-caught vs. captive-born gibbons to certain stimuli, like different kinds of music.

Blair gives a welcome back scratch to Elizabeth, who peeps over her shoulder at her newest caregiver.

Her Washington experience was frustrating for her, in that she would see good bills sitting stalled in Congress for years on end, so she feels that education is the key to making progress for animals and the environment.

These days, though, it sometimes seems that “science is progressing faster than the public can keep up with it,” she says. And she sees some of her friends talking about the environment in ways that (she hopes) they wouldn’t if they knew more about how the world works.

“The natural world is dynamic, and extinction happens, but if harm is being done because of us, it’s our responsibility to stop it. And habitat degradation is the leading cause of extinction now,” she says. From her studies of the Peaks of Otter salamanders, which are confined to a 12-mile stretch of the Appalachians not far from her college, she has witnessed what short-sighted human activities like clear-cutting can do.

“Some of my friends think that extinction is just part of ‘the plan,’” she says, but in general she feels that her peers are increasingly talking about things like climate change and biodiversity conservation. “At least we’re having these conversations.”