Speaking up for lab monkeys

Today is the last day to submit a comment in support of a Rulemaking Petition to improve conditions for U.S. lab monkeys. This opportunity (which had been extended two months) expires at 11:59 PM, so don’t delay, and please share with your friends.

Here’s a sample comment to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Please feel free to add your personal touch:

I support this petition to create strict, enforceable regulations that promote the psychological well-being of all primates in labs. Monkeys are intelligent, group-living animals, just like humans, and need to be housed with others of their kind in order to maintain their physical and psychological health.

In addition,all primates living in captivity deserve an enriched, stimulating environment where they can freely carry out natural behaviors. Decisions about the appropriate level of enrichment should not be simply left to the laboratory veterinarians, as such decisions have in the past; house vets may well have an inherent conflict of interest, leading them to wish to minimize costs for their employer.

Although the Animal Welfare Act requires minimum standards of care to “promote the psychological well-being of nonhuman primates,” these vague regulations have proven to be difficult to enforce. It is time to update the AWA.

IPPL’s founder and executive director Shirley McGreal has submitted a substantial letter of support for this petition. Here is the full text, below:

*****

August 31, 2015

Dear Dr. Clarke:

I am offering this statement in response to APHIS Docket No. 2014-0098, “Rulemaking Petition to Develop Specific Ethologically Appropriate Standards for Nonhuman Primates in Research.” Last year I submitted a declaration in favor of the petition during an earlier stage of the rulemaking process. Now I would like to voice my continued support for the petition’s request that the Animal Welfare Act (AWA), as amended in 1985, be further refined to include clear standards and definitions that will truly promote the psychological well-being of primates being kept in laboratories. Enforceable minimum standards are essential to replace the vague guidelines currently in place. Although some progress has been made over the past 30 years, the AWA mandate of 1985 has not resulted in substantially improved care for most of the tens of thousands of monkeys currently housed in U.S. research facilities.

I received my doctoral degree from the University of Cincinnati in 1971. However, I would like to comment from my expert perspective as the founder and executive director of the International Primate Protection League (IPPL), a grassroots advocacy organization I created in 1973. I continue to act as IPPL’s Executive Director and oversee the daily operations of the gibbon sanctuary I established in South Carolina in 1977. Thus, I have nearly four decades’ experience in operating a facility where the needs of the nonhuman primate residents are paramount.

In addition, I have witnessed the lingering impact of poor laboratory husbandry practices on a number of retired lab gibbons in my care. The IPPL sanctuary is now home to 36 gibbons, most of them rescued and retired from previous lives as display animals in entertainment venues, as pets, and as research subjects. Over the years, our residents have included 13 gibbons who came to IPPL from labs, eight of whom are still with us.

I have also, throughout my career, had a particular interest in the impact of human activity on monkeys commonly used for research: I have gone undercover to see for myself the conditions experienced by monkeys used for experiments and traveled extensively in primate habitat countries, where I have had the opportunity to observe wild monkeys as well as those who have been rescued from unfortunate captive conditions and placed in reputable sanctuaries.

My expertise with gibbons in particular leads me to point to these primates as “the exception that proves the rule” with respect to the above-referenced petition. Gibbons are small-bodied and are thus often mistaken for monkeys by the general zoo-going public. But gibbons are, of course, not monkeys at all (as are the vast majority of the estimated 110,000 primates in U.S. labs). Still, I know that our gibbons benefit greatly from having access to enhancements to their captive environment that promote psychological well-being, such as those we offer at the IPPL Headquarters Sanctuary.

Such enhancements are analogous to what these little apes would be able to experience in nature. Examples include: free access from their night quarters to spacious outdoor enclosures and the ability to enjoy fresh air and sunshine (on all but the coldest winter days), the opportunity to choose a compatible opposite-sex companion with whom to pair-bond (as is typical for these monogamous animals), a wholesome diet consisting primarily of fresh fruit and vegetables (which varies daily and seasonally), the ability to engage in preferred locomotor behaviors (in their case, perching and brachiating well above the ground), regular provision of enrichment (of a type suitable for their relatively non-dexterous fingers), and a separate enclosure for each family at least partly shielded from others by visual barriers (as preferred by these territorial apes).

While we have made many modifications to our sanctuary environment to meet the distinctive requirements of our residents, we have also taken care to meet the special needs of particular individuals. For example, Igor was an elderly lab veteran whose arm muscles were damaged from repeated self-biting. We provided him with a smaller outdoor enclosure that would allow him freedom of movement without risking injury due to falling from a great height.

Our supporters are welcome to visit our facility by appointment and see for themselves the enhancements we have put in place. The fact that we have had a number of gibbons live well into their fifties while under our care speaks for itself. Over the years, we have made numerous improvements to our sanctuary on a budget that relies entirely on donations from individuals and grants from foundations. Surely our nation’s research laboratories, with their access to substantial investment and government funding, can manage to do the same.

With respect to the questions asked by the USDA/APHIS in the Federal Register:

- Should APHIS amend § 3.81 of the AWA regulations to require research facilities to construct and maintain an ethologically appropriate environment for nonhuman primates, and specify the minimum standards that must be met for an environment to be considered ethologically appropriate?

Yes, APHIS should amend § 3.81 of the Animal Welfare Act to require that research facilities construct and maintain an environment for the nonhuman primates in their care that promotes a full range of positive, species-typical behaviors. Clear, minimum husbandry standards that would be enforceable by APHIS inspectors should be put in place without delay. Such standards were recently accepted by the National Institutes of Health for the care of lab chimpanzees, a strong indication that formulating such regulations is not beyond our current capabilities. To postpone the “trickling down” of similar standards to other primates implies that they are less worthy of ethical consideration than are apes—a stance I strongly deny, as will anyone who is aware of the growing body of data that demonstrates the behavioral and psychological complexity of “mere monkeys.”

- What constitutes an ethologically appropriate environment for a nonhuman primate? Does this differ among species of nonhuman primates? If so, how does it differ?

An ethologically appropriate environment should consist of one in which the animals are able to express as many of their species-typical behaviors as possible, to the extent that such behaviors are consistent with an ethos of responsible caregiving. The result should be a reduced production of stereotypical behaviors and other measures of chronic stress.

Part of that charge means providing an environment analogous to what primates would encounter their natural habitat (e.g., social companions, durable and destructible manipulanda, a complex living space with visual barriers, and so on). These enhancements need not always mimic nature directly, as certain non-natural stimuli (such as computer games, music/videos, and positive human-nonhuman primate interactions) have sometimes been shown to compensate for the deficiencies of the captive environment in a cost-effective way.

Of course, primates living in a state of nature must contend with environmental hazards that would be foolish to replicate in a captive setting. Given that we are inescapably robbing lab monkeys of a significant measure of self-determination for their entire lives, however, a little compensation in terms of decreased exposure to predation, parasitism, and seasonal inanition seems reasonable.

Yes, an ethologically appropriate environment would differ among species. Some primates are arboreal, some are terrestrial, species-typical social structures vary, and so on. But we would not need to create standards for all 600-plus currently recognized primate species and subspecies. There are perhaps only two dozen species used in U.S. laboratories, and it should be feasible to draw up husbandry standards for these well-studied taxa. In addition, although there is significant diversity within the primate order, certain broad commonalities exist, too, such as the impulse to be part of a social group and the desire to have agency in daily life, enabling one to exert some control over the immediate environment.

Our understanding of what constitutes an ethologically appropriate environment for the animals in our care will continue to evolve and improve. But this should not prevent us from moving forward with our best current understanding of what primates require to thrive in a captive setting. Just as we have incomplete information concerning what constitutes a healthy human diet (eggs or no eggs? low fat or healthy fats?), this has not prevented us from seeking to adopt and encourage positive changes consistent with our existing level of knowledge.

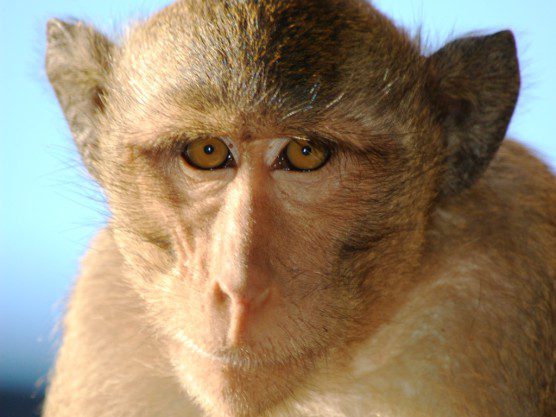

Some primates, such as macaques, are very adaptable, it’s true. Unfortunately, in the past this has meant that they were able to adapt to a very poor quality of care and still survive in the most barren and unaccommodating of settings—solitary, bald, twitchy, and miserable—for years. We should not permit some monkeys’ natural resilience to excuse us from providing the best captive environment we can.

- Are there any environmental conditions that make an environment ethologically inappropriate for a nonhuman primate? If so, what are they? Do they differ among species of nonhuman primates?

Yes, there are conditions that would be considered ethologically inappropriate for captive primates generally: solitary housing in a low-stimulus (barren) environment would be unacceptable. In addition, some measures regarding what is appropriate would vary depending on species. For example, same-sex adult gibbons do not normally tolerate one another in close proximity (unlike, say, macaques, which thrive on it). However, such variations are generally well-documented in the literature, and regulators should have little difficulty recognizing such idiosyncrasies and reflecting them in any forthcoming regulations.

- Does an ethologically appropriate environment for nonhuman primates used in research differ from an ethologically appropriate environment for nonhuman primates that are sold or exhibited? If so, in what ways does it differ?

No, for the most part the obligation to provide an ethologically appropriate environment for a captive primate should be similar for researchers, dealers, and exhibitors. Primates held in captivity are not aware if they are being kept for purely research, commercial, or entertainment purposes, and it’s their perspective we are trying to take with reference to this petition.

- Who should make the determination regarding the ethological appropriateness of the environment for nonhuman primates at a particular research facility: The attending veterinarian for the facility, APHIS, or both parties? If both parties should jointly make such a determination, which responsibilities should fall to the attending veterinarian and which to APHIS?

The primary determination concerning compliance with the AWA should rest with the USDA/APHIS inspectors. While the attending veterinarian at each facility will of course play a major role in the formulation of an environmental enhancement plan unique to his/her institution, such individuals will unfortunately also be likely to experience a conflict of interest in developing such a plan: an investment in the well-being of the animals vs. the need to keep an eye on the bottom line. USDA/APHIS inspectors are necessarily relieved of such a conflict, and the ability to judge impartially whether the needs of the animals are being met is best left to them.

Currently, environmental enhancement plans need not be approved by the USDA and are not available for public review. While the AWA mandates the promotion of psychological well-being in captive primates, a relaxing of criteria to the lowest common denominator can happen when convenience and cost are weighed against vague or poorly defined regulations, resulting in compromised care. The point of creating engineering standards is not to insist on a one-size-fits-all approach to primate husbandry that fails to take advantage of human rationality and ingenuity. The point is to steer lab practices away from the current default, which is a perfunctory approach to primate well-being.

My view is that we should not settle for providing lab primates with minimally adequate husbandry. Instead, we should aim to give all primates within our care access to an optimal captive environment, one that is appropriately tailored to their long-term needs.

Thank you for your consideration.

Shirley McGreal, Ph.D., OBE

Founder and Executive Director

International Primate Protection League

Summerville, South Carolina

Time to end animal experiments for good

It seems only logical and painfully clear that living sentient creatures deserve these basic life rights. I am begging on their behalf.

Yes, indeed. The public comment period is now closed, but I see that 10,117 comments were logged. In preparing for submitting IPPL’s own comments, I read about a 1997 survey that “some facilities considered enrichment plans adequate simply with the provision of ‘one perch, one rubber toy, and a few grapes now and then for each singly caged primate.'” That was 12 years after the Animal Welfare Act was specifically amended to say that labs are supposed to promote the psychological well-being of the primates in their care. For the last 30 years, the problem has been that the current AWA guidelines are so vague as to be unenforceable. This petition would demand concrete regulations that can be enforced by USDA inspectors. Until the 110,000 monkeys in U.S. labs can be freed and experiments on them brought to and end, it seems to me that we at least owe them more than a few grapes now and then.